Theologically Liberal or Conservative?

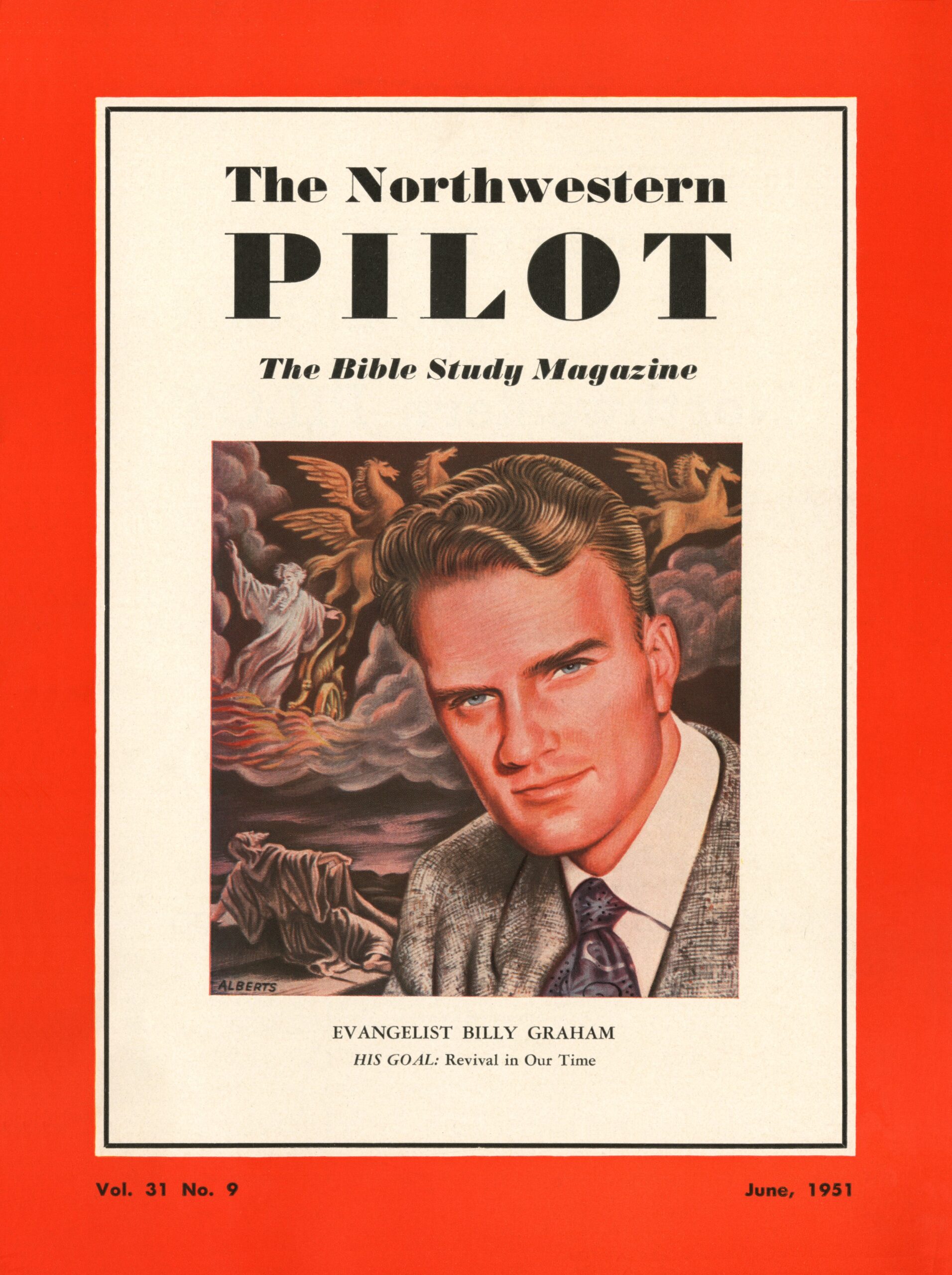

Billy Graham was in a tough spot. He was a young upstart evangelist who had (perhaps against his better judgment) accepted the call to become the president of Northwestern Schools upon the death of W. B. Riley in late 1947. Since its founding in 1902, Riley had been the head of Northwestern as it developed from a small Bible and missionary training school into a seminary and college. The Northwestern Schools emerged in a culture that was enamored with the possibilities of progress. Industrial progress, social progress, political progress, even religious progress seemed inevitable. Many thought that for Christianity to be relevant to the modern world, it had to adapt and evolve, to shed outmoded and traditional beliefs like the Trinity, the virgin birth of Christ, or the innate sinfulness of humans. What did Christianity look like after shedding such beliefs? In the poignant words of H. R. Niebuhr, it was a religion where “A God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a cross” (The Kingdom of God in America, 1937, p. 193). This kind of religion is what we now call theological liberalism. It subverted traditional Christian doctrines about God, Christ, humanity, and salvation in favor of beliefs that were determined by a modern optimistic view of human potential and progress.

The currents of theological liberalism arrived suddenly in American denominations and schools. In the early twentieth century, Baptists like W. B. Riley and Presbyterians like J. Gresham Machen found themselves at the front of a resistance to an influx of liberalism in their own churches and schools. The core difference between theological liberals and conservatives like Riley and Machen was that liberals denied the divine inspiration and authority of Scripture. For them the Bible was inspired in the same way that one might say Shakespeare was inspired. It was filled with compelling human stories, but it wasn’t God’s infallible and inerrant word. Thus, the content of the Bible could be revised or rejected, assimilating it to modern cultural values. By contrast, theological conservatives emphasized the divine nature of Scripture and its authority. Rather than be shaped by culture, Scripture, they argued, must shape culture.

Since its founding in 1902, no theme has animated the existence of Northwestern more than the belief that “the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments are verbally and plenarily inspired of God, are inerrant in the original writings, and are the infallible authority in all matters of faith and conduct (2 Timothy 3:16)” (UNW Doctrinal Statement). This commitment to a high view of Scripture and to the traditional Christian beliefs it entails is the hallmark of Northwestern’s culture. Even today, as a voluntary community, all employees and faculty members affirm their commitment to the UNW Doctrinal Statement with the understanding that UNW is “theologically conservative and evangelical in doctrine.”

Many things about Northwestern have changed over the last 122 years, but one constant that unites our history is as strong today as it was in 1902: Our conviction that Scripture is God’s Word to us—his infallible and inerrant Word—in which we come to know the Word Incarnate, Jesus Christ. This UNWavering commitment positions Northwestern firmly within a theologically conservative evangelical tradition.

Separation or Cultural Engagement?

By 1949 when Billy Graham became a household name, the division between theological conservatives and liberals was well established. Conservatives had created their own institutions—denominations and schools that remained faithful to the fundamental doctrines of Christianity. However, the conservative fundamentalist movement, which Riley attempted to pass on to Graham, was fracturing. Isolationist and separatist features became more common amongst fundamentalists. Rather than engage culture, fundamentalists tended to withdraw from it. But as Graham took the reins of Northwestern, a new set of leaders emerged with him, wanting to steer fundamentalism away from separatism and back toward a renewed mission of cultural engagement.

Those leaders (e.g., Carl F. H. Henry, Harold Ockenga, Charles Fuller) were dubbed the neo-evangelicals or new evangelicals. They helped establish many of today’s most recognizable parachurch organizations: the National Association of Evangelicals (1942), Youth for Christ (1944), InterVarsity Press (1947), Fuller Theological Seminary (1947), Evangelical Theological Society (1949), Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (1950), World Vision (1950), World Evangelical Fellowship (1951), Campus Crusade for Christ (1951), Young Life (1953), Fellowship of Christian Athletes (1954), and Christianity Today (1956).

Graham himself exemplified the evangelical impulse to share the Gospel of Jesus Christ, but the new evangelicalism was more than evangelistic preaching. It attempted to reengage with intellectual and cultural issues as evangelicals had done in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The new evangelicalism envisioned by Graham and others took the concerns of both this world and the next seriously. They believed that scientific discovery and social action were not at odds with traditional Christian faith. In fact, the opposite was true. The Christian faith provided them with the right lens to understand the truth, goodness, and beauty of God’s creation, and it called them to serve the poor and oppressed as Christ had done.

It was a tough sell. Some of the separatist-minded fundamentalists at Northwestern believed that any concern for the poor or appreciation of non-Christian culture meant that one was secretly liberal. Graham did not escape that suspicion. But with clear-eyed conviction, he challenged Northwestern to engage for the sake of the Gospel. On the evening of June 13, 1950, in his annual report to Northwestern’s board of trustees, Graham said: “Your responsibility tonight is not only to counsel and advise, but to come to the point of decision and to be absolutely certain that this institution keeps to the objectives of our great and illustrious Founder. Within 12 months we have entered a new spiritual era. This is a new day. There are new issues to be faced, new problems to be concerned with. This is the age of atomic power, of the television, and also a day of revival.”

Graham’s challenge to the board that night remains our challenge today. “There are new issues to be faced, new problems to be concerned with.” But today is not just the age of atomic power and television. It is an age of genetic enhancement and artificial intelligence—an age where technology blurs the lines between reality and fiction, between the human and the algorithm. It is an age of anxiety, not because of the threat of nuclear winter but because of the threat we carry in our pockets. What does cultural engagement look like for Christians today? How should we act in the world? How can we address the crises of our age with the hope of the Gospel?

Northwestern’s Vision for Cultural Engagement

Throughout the ages, God’s people have wrestled with varying convictions regarding engagement in the world —both the definition of as well as the degree to which Christians ought to be engaged in the world. The spectrum of engagement runs from one extreme of cultural assimilation (liberalism) to the other extreme of cultural separation (fundamentalism). So where in this spectrum does Northwestern fall and why?

Vision 2030 states, “By 2030 Northwestern will be a nationally recognized voice that shapes society and speaks into contemporary culture, influences how people think, and equips Christian leaders for lives of purpose, service, and civic engagement through the transforming power of Christian higher education and Christian media.” This vision encompasses the breadth of the entire organization, which includes the University of Northwestern and Northwestern Media. In fact, both parts, working in strategic collaboration, make this vision achievable.

Our position as a theologically conservative evangelical Christian university and media enterprise anchors us with an UNWavering commitment to Scripture. And our vision to shape society, to speak into contemporary culture, and to influence how people think and act acknowledges that we are located at the epicenter of a deeply secular culture in need of the goodness, truth, and beauty of the Gospel. In our commitment and vision, we remain on the faithful trajectory that Riley and Graham set for Northwestern.

Dutch theologian, Abraham Kuyper, famously declared, “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is sovereign, does not cry, ‘Mine.’” Every part of this fallen creation falls within God’s redemptive activity: both people as well as the cultural spheres in which we live.

Through our vision, Northwestern will prepare leaders who are called and equipped to seek lost people and serve in every square inch of culture. But why? Don’t we risk being corrupted and polluted by the world? Shouldn’t Christians instead pursue a quiet, private, and simple life far from the reaches of secular culture and the fabric of society where we can preserve Biblical orthodoxy (what we believe) and orthopraxy (how we must live) within our families and churches? This is a valid question, but it is a strategy that risks losing our calling to be salt and light in a world that needs Christ.

Without question, we are to avoid worldliness and becoming polluted by the world. However, the resounding call of Scripture is to prepare leaders who are anchored in their faith and doctrine, who demonstrate impeccable character, who are skilled in their craft, and who confidently go into the world and amplify the Gospel, which transforms lost and broken people as well as lost and broken cultural spheres.

Perhaps no other passage in Scripture captures our status as “strangers and exiles” (1 Peter 2:11) quite like Jeremiah 29:4–7. These verses form part of a letter that the prophet Jeremiah sent to God’s people who were exiled in Babylon—a godless, corrupt, and hedonistic culture not unlike our own. We must understand that the Israelites were bound to Levitical laws of purity and cleanliness. How were they to live in Babylon without capitulation or compromise? The obvious thing to do would be to isolate and separate themselves from Babylonian society as much as possible. But this is not what God directs them to do. Rather, Jeremiah writes, “This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel says to all those I carried into exile from Jerusalem to Babylon: ‘Build houses and settle down; plant gardens and eat what they produce. Marry and have sons and daughters; find wives for your sons and give your daughters in marriage, so that they too may have sons and daughters. Increase in number there; do not decrease. Also, seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you into exile. Pray to the Lord for it, because if it prospers, you too will prosper’” (Jeremiah 29:4–7).

Verses 4–6 describe how the Israelites should develop and increase their own community. And verse 7 charges them to desire not only their own welfare but also the welfare of the Babylonian community. While Babylon was an instrument of God’s righteous judgement on the Israelites, the Israelites were instruments of God’s grace for Babylon. What a beautiful picture of God’s sovereign rule over all the nations of the world and an illustration of His love for His own people as well as the lost. Rather than live with hostility and resentment toward their captors, the Israelites were to seek their happiness. God was fulfilling his promise to Abraham despite all indications to the contrary. He was forming his people and through them blessing the nations (Genesis 12).

As Christians, we recognize that the ultimate fulfillment of this promise is found in Jesus Christ, who, though being holy and righteous, nonetheless came to dwell in the midst of sinful humanity. He was not corrupted by our impurity, but he purified us through the cross. Christ calls us to imitate him: to be a faithful and holy presence as individuals and as the church in every sphere of life and culture.

How does this apply at Northwestern? Here’s what I, as the president of Northwestern, deeply believe about how God is calling us to live in the world today.

First, we will remain UNWavering in our commitment to Scripture as the inspired, inerrant, infallible, authoritative, and sufficient word of God. On this conviction, Northwestern will change nothing. In every academic endeavor and discipline, and in our media ministry, we begin with this truth as ground zero. Cultures shift and sway, “but the Word of the Lord endures forever” (1 Peter 1:25). Therefore, we will live in humble and faithful dependence on and submission to Scripture.

Second, we continue our UNWavering commitment to serve the needs of God’s world with love. This is what cultural engagement means. We are compelled to lead through service and love—meeting needs and solving problems in every square inch of culture. To that end, we will prepare God-honoring leaders who reflect the excellence of Christ in every cultural sphere: engineering, science, art, filmmaking, media, government and politics, computer and data science, business, education, and of course, vocational Christian scholarship and ministry.

The history and vision of Northwestern compels us to pray for, and to seek, the peace and welfare of the cultures and communities in which we are called to live. May Northwestern be an outpost of God’s shalom in a weary world! I believe we are called to this kind of life. It is not a simple life, nor a safe life. But confidently in the truth of God’s Word, we will amplify the Gospel to God’s world.